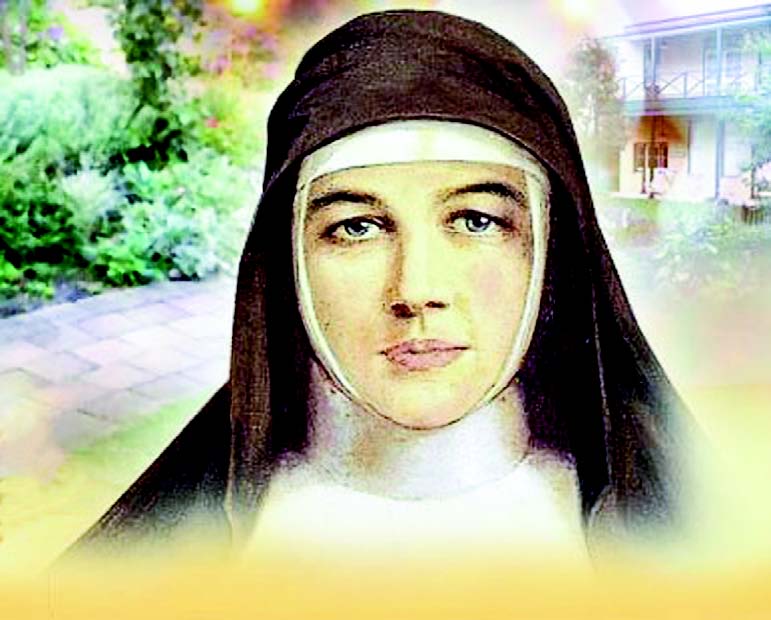

St. Mary of the Cross MacKillop, first Australian saint

Monday, November 30, 2015

*Rogelio Zelada

Mary MacKillop represents the unique and singular case of a nun who received the recognition of sainthood despite having been excommunicated.

In the silence of the afternoon, Sister MacKillop has read once more the letter from Laurence Sheil, bishop of Adelaide, who has just expelled her from the Church. He has excommunicated her and all the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Sacred Heart, deprived them from receiving the sacraments, and forbidden them to continue their teaching and the practice of charity to the poor.

Born in Melbourne in 1842, of Scottish parents, Mary Helen MacKillop founded in 1866, with the support of Father Julian Woods, the first Australian women's religious community, the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Sacred Heart. Mary Helen started with a small school for poor and illiterate children, which opened in an old stable in Penola. In just five years, it had gathered a thriving congregation of 160 young religious, the "Josephites," dedicated to schools, orphanages, shelters for the homeless, destitute and elderly, the rescue of prostitutes and the reintegration of prisoners into society.

The Josephite sisters were born from the heart of Sister McKillop with a clear dynamic spirit, driven from the outset by the urgency of educating the poorest children in the rural areas and meeting the growing needs of the colonies in the vast territory of the Australian Outback. It is a huge area south of the continent, arid and almost uninhabited, where small farming communities are emerging, impoverished camps to house the builders of railroads and mining settlements, where there are many children to educate, and sick and the elderly to care for. The Josephites work in isolated areas, where the presence of priests is not permanent. The live in poverty, as do the townspeople, unpretentious and without amenities. They live in tents, sheds and shacks, very close to the poor, sharing with them while encouraging them.

For Bishop Sheil, the work of the religious women seemed daring – mainly the decisions of Sister Mary – especially since they were outside his control. He was not sympathetic to this nun who had questioned on more than one occasion an ill-advised decision of the bishop in relation to new foundations and the work of the congregation.

The bishop, of unpleasant character and not really open to dialogue, gave credence to rumors and criticism from members of the local clergy who, angry at Sister MacKillop, lied to the bishop and predisposed his mind against the nun. They blamed her for having denounced the scandalous conduct of a priest known to them, who had finally been suspended from ministry and returned to his own country. Bishop Sheil accused Sister MacKillop of "insubordination" and immediately excommunicated her. Those were five terrible months, where the good work that the religious woman had done seemed to collapse every day.

Her unconditional defenders were the Jesuit priests who, from the first moment, understood the injustice and illegality of the sudden excommunication and always gave their support and spiritual care to all the sisters. On his deathbed and sorry for all the harm he had done, Bishop Sheil lifted the excommunication of Sister MacKillop who, like Fray Luis de Leon, continued her work as if nothing had happened.

In 1873 she traveled to Rome and received a pontifical approval from Pope Pius IX; from that moment, the congregation acquired the necessary autonomy to carry out its mission. New foundations flourished not only in Australia, but also in New Zealand, Ireland, East Timor and Peru, where they work with the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, especially immigrants and natives.

She, who in her religious profession had taken the name of Mary of the Cross, died in 1909 in a convent that she founded north of Sydney, as a result of a brain hemorrhage she had suffered eight years before. Fragile and motionless, she spent this last stage of her life in prayer and accepting her physical disability.

Since her death, Australians revered her as a symbol of their Catholic identity. Her cause for beatification began in 1973; in 1992, she was declared venerable by the recognition of her heroic virtues. Pope John Paul II beatified her in 1995. During World Youth Day, Pope Benedict XVI prayed at her tomb and presented her as a model for the youth of the world; Pope Benedict XVI himself canonized her on Oct. 17, 2010. At the ceremony, he noted that St. Mary Mackillop "was dedicated from her youth to educating the poor in the difficult landscape of rural Australia.”

This is the unique and singular case of a nun who received the recognition of sainthood despite having been excommunicated. She made the long journey to holiness from a very small town, from a poor stable, without means, without human resources, but with the enormous power of faith and an unwavering trust in the providence of God.

Comments from readers