Alfonso X 'the Wise': translator of the Gospels

Monday, November 4, 2019

*Emilio de Armas

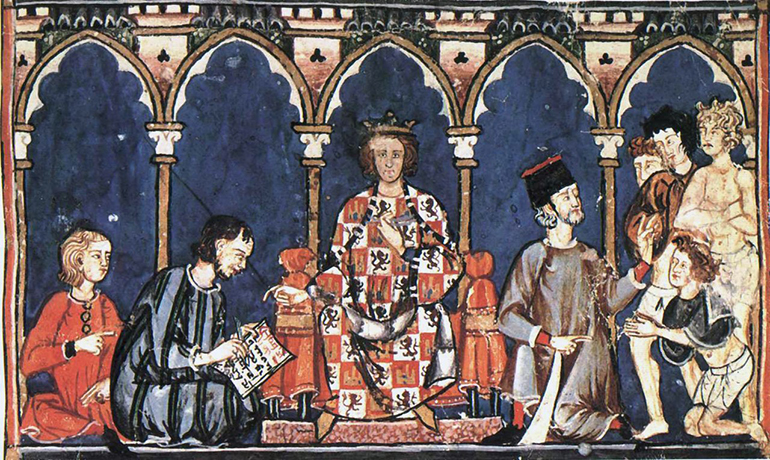

Alfonso X the Wise with his collaborators in the royal scriptorium.

Alfonso X of Castile, called “the Wise” because of his vast knowledge and great contributions to Spanish culture in the Middle Ages, was born in Toledo, Spain, Nov. 23, 1221. He was the first-born son of King Ferdinand III, “the Conquistador” and “the Saint”, and received his father’s crown as his inheritance. He ruled over Castilla, León, Toledo, Galicia, Sevilla, Córdoba, Murcia, Jaén and Algarve (since 1260).

Upon the death of Ferdinand III, Alfonso renewed his father’s offensive against the Moors who occupied great swaths of Spanish territory. He occupied Jerez (1253), ransacked Salé, the port of Rabat (1260), and conquered Cádiz (circa 1262). In 1264, he had to confront an important uprising of the Mudejars of Murcia and the valley of the Guadalquivir.

As the son of Beatrice of Swabia, he aspired to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire, a project to which he dedicated many fruitless gestures for nearly half his reign.

Illuminated manuscript of Alfonso X the Wise (about 1250)

He carried out active and beneficial economic policies: he reformed the coin and the hacienda (estate), granted numerous holidays and recognized the Honorable Council of the Mesta (a group of cattle ranchers in the Iberian Peninsula). But his most durable contribution to Spain were his literary, scientific, historical and legal works, accomplished through his royal scriptorium (literally, “a place for writing” or more specifically, a corps of specialists dedicated, in this case, to the translation and editing of texts under the supervision of the king.)

Alfonso X funded, supervised and often participated, with his own writings and in collaboration with a group of erudite Christians, Jews and Muslims known as the School of Translators of Toledo, in the composition of a great literary output that, to a large degree, gave rise to Spanish language prose.

Exercising great religious tolerance, he ordered the translation of the Quran and the Talmud to Spanish, and he valued being considered “the King of the Three Religions.” His scriptorium also translated numerous cultural works universally known at the time. In addition, he wrote the “Cantigas de Santa María” (Songs to St. Mary) and other poems, through which he made a great contribution to the cultured language of the time in the royal court, the Galician-Portuguese.

The last years of his rule were convulsed, however, due to the conflict over succession provoked by the premature death of his first-born, Fernando de la Cerda, whose children had yet to reach their majority. This resulted in open rebellion by Alfonso’s second-born, Prince Sancho, along with a great number of the nobles and cities of the kingdom. Alfonso X died in Sevilla April 4, 1284, amid that turmoil.

Among the numerous translations to the Spanish language executed under his direction and at his urging, are found the four canonical Gospels (1260). This work amply preceded that of Martin Luther, King James, and all the other European translators of the Bible. Alfonso’s work thus gave rise to the first version of such texts in what was considered at the time a “vulgar language,” that is, the vernacular; different from the Greek and Latin accepted by the Church. Although opposed to any translation of Sacred Scripture to the vernacular, the Church did not object — for very royal reasons — to the monarch’s enterprise, and the so-called Manuscrito Escurialense, which contains the four Gospels written in Spanish by the royal scriptorium of Alfonso X, under his supervision, would become a veritable cultural treasure of Spain and Europe.

Unfortunately, however, King Alfonso X’s translation did not emerge from the dusty Spanish archives until the second half of the 20th century, when the Protestant translations were well known all over the world. The first edition of the Gospels in Spanish by Alfonso X was not printed until 1970: a book known as The New Testament according to the Escurialense Manuscript 1-1-6 (Añejos of the Library of the Royal Spanish Academy, 22), by Thomas Montgomery and Spurgeon (Spud) Baldwin, Madrid, Real Academia Española, 1970.

For this reason, the text continues to be almost unknown nearly eight centuries after its writing. A digital reproduction, created by the Reformed Church, can be read here: http://www.iglesiareformada.com/Alfonso_Lucas_Parte_1.html.

Both of these textual sources have been used by Emmanuel Publisher, which also prints La Voz Católica, the Spanish language newspaper of the Archdiocese of Miami, to edit the book El Santo Evangelio según San Lucas (“The Holy Gospel According to St. Luke. Version of King Alfonso X the Wise (year 1260)”.

This book is available for anyone interested in the process which gave rise to the development of Spanish prose and the diffusion of the Gospels in all the languages on earth.

Comments from readers