In hoc signo vinces

Monday, April 22, 2019

*Rogelio Zelada

The restlessness that floats in the dawn air shakes the solid half-century-old wall with which emperor Aurelian encircled the great city of Romulus and Remus, because the war between the Romans has arrived at the very doors of the city. Of the four Augustans who shared power over the empire, the Orientals —Maximianus and Galerius— disappeared from the political and military scene by the end of the year 307. Now the tensions, the struggle for absolute power and the political ambitions of the other two emperors of the West, Constantine and Maxentius, have brought Rome to the brink.

Maxentius, who remains encamped and well protected behind the walls, has an army numerically superior to that of Constantine, but does not dare to face him because the imperial augurs predicted certain death if he came out of the fortified enclosure.

Finally, the desire to engage in combat was stronger than superstitious fear, so the legions of Maxentius, determined and certain of victory, run to the Via Flaminia toward the Milvian Bridge for the great battle.

Flavius Valerius Aurelius Constantinus was born in Naissus, now Nis, Serbia, on February 27, 272, the son of Constantius Chlorus and Helena. A military strategist, he arrived in the Eternal City in search of the imperial laurel after great military victories over the Germans, the Persians, the Picts and the Alemanni.

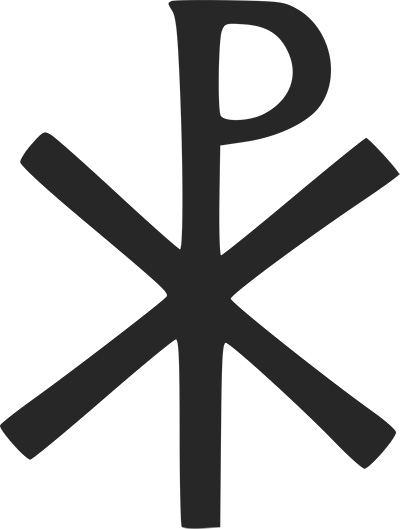

The Chi Rho: "In hoc signo vinces!" ("With this sign thou shalt conquer!")

On October 28, 312, Maxentius was defeated and his head returned to the city nailed to a labarum, the military standard of the troops of the new and absolute world emperor. Tradition or legend says that before the battle, Constantine had also received a marvelous oracle, different from that of Maxentius: He saw a great sign in the sky, shining brightly, and clearly heard words coming from beyond: “In hoc signo vinces!” (“With this sign thou shalt conquer!”). The wonderful vision was not a cross but the Chi-Rho, the anagram of the name of Christ in Greek, a badge that would appear on the imperial labara and on the banners that the victorious legions carried in their triumphal entry.

The great victory of Constantine was the beginning of an era of freedom for the Christian faith. In Milan, on June 15, 313, he drafted a protocol of political intentions and procedures now known as the “Edict of Milan,” a statement written in terms beneficial to Christians, granting not only a total and complete freedom of worship, but also the return of all the goods that had been confiscated during the persecutions.

“As far as divine things are concerned, it is necessary to allow each one to obey the dictates of his conscience. We want anyone who wishes to follow the Christian religion to do so without fear of being disturbed.”

At the time, the number of Christians throughout the Roman Empire had grown tremendously: from about 40,000 in the year 150, to 6,300,000 —more than 10 percent of the total population. It is the beginning of a new situation for the Church, to be suddenly protected and cared for by the highest earthly power.

Constantine donated to Pope Sylvester I the palace that had belonged to Diocletian, a great persecutor of Christians, on the property of the Lateran family, where the first great basilica for Christian worship was built. The barracks of Maxentius' Praetorian Guard had been there. The place, once finished, became the cathedral of Rome under the invocation of St. John: St. John Lateran.

A great basilica was built on the Vatican hill, above the mausoleum of Gaius, where the relics of the first pope were kept. For this, the slopes of the hill had to be filled with tons of stone to make a solid base for the great building, although this architectural tribute meant the disappearance of the cemetery of the wealthy Romans located in that hillside.

In addition to freedom of worship and the restitution of confiscated property, money was distributed as compensation for the damages received. Fiscal exemptions were applied. Not only were churches rebuilt, but basilicas were erected everywhere, their construction paid for by the imperial family. More than 40 buildings for Christian worship were built in Rome alone.

In the year 315, the anagram of Christ appears on Roman coins, replacing the effigies of the gods. Ecclesiastical sentences acquire civil validity. Christians reach high positions in government, and sacrifices, magic, augurs and all pagan worship are prohibited. Many Christians were convinced that the Kingdom of God had arrived or was about to burst forth.

However, it is not possible to call Constantine a Christian. As a soldier, he worshiped the god Mitra, a solar deity whose cult coincided with that of the Christians on the first day of the week. Rather, he saw himself as “protector” of the Church and firmly believed that its duties and obligations did not allow him to act according to what he expected and needed to consolidate his power as emperor. Because of intrigues in the court, he executed his older son, Crispus, and his second wife, Fausta, shortly after.

However, he awarded the title of Empress to his mother Helena, who had been disowned by his father, and this holy woman often tempered Constantine’s decisions.

Seriously ill, his last wish was to die as a member of the Church he had wanted to defend and protect as a pagan. He was baptized in Nicomedia, Turkey, on May 22, 337, after ruling an immense and powerful empire in a fierce and totalitarian way for 31 years.

So began a time of challenges for the Church, of searching for authenticity, of retaining the identity and depth it had acquired during the great crucible of the persecutions. Anchorites, hermits, monks, men and women searching for authenticity will go to the desert and the solitude of caves and mountains to live in austere poverty the heroic ideal of faith. They do not want a comfortable Christianity. They long for the time when faith in Christ, the living out of the Gospel, entailed constant challenge; a way of being, of thinking and acting, that allowed them to face even death with the inexhaustible force of hope.

Comments from readers