Fray Jun�pero

Monday, March 2, 2015

*Rogelio Zelada

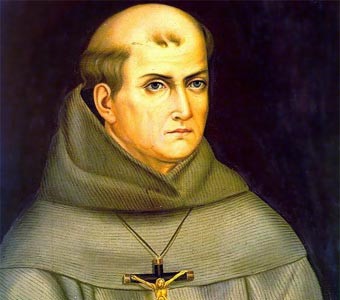

Fray Junípero Serra

The hoarse thunder of the cannons on starboard shakes the sturdy ship anchored in Monterey Bay; the salute, repeated every half hour, joins the tolling of the bells of the Mission San Carlos Borromeo, as if longing to join the prayer of the indigenous people and Franciscan friars who have come from all the neighboring missions.

It’s the morning of August 28, 1784, and Fray Junípero Serra has departed this life at age 70: 54 of those years in Franciscan life, and 35 of unceasing missionary work from the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro to the sierras of Alta California, territories that he evangelized almost entirely on foot.

Fray Junípero walked more than 10,000 kilometers to announce and spread the faith of Christ among the Pames and Apache people. He baptized almost 8,000 converts and confirmed more than 5,000 in the nine missions he founded for the salvation and advancement of the indigenous people.

Born in Petra, on the island of Mayorca, amidst a very Christian family of farmers, Miguel José Serra Ferrer was a weak child who grew up with poor health. But this did not hamper his entrance in the Franciscan order when he turned 17. Even though he was barely able to do hard labor at the convent, he made his religious profession in 1731 and took the name of Fray Junípero, one of those who formed the first group of Friars Minor. Eleven years later he received with honors a doctorate in Sacred Theology and a professorship at the University of Palma.

An outstanding professor and a great preacher of clear and simple words, Fray Junípero takes every opportunity to go and preach missions in the numerous parishes and convents on the island. One of his disciples wants to leave for the missions, something that ignites in him the desire to take the Gospel to places “over 300 leagues away from Christendom.” After obtaining permission from his superiors, he embarks to the New World with 20 of his order’s friars and seven Dominicans.

After a two-month voyage, they arrive at San Juan of Puerto Rico, and continue their trip until they finally disembark in Veracruz. Fray Junípero forgoes the carriages and the horses, preferring to set out toward Mexico on foot, following the purest Franciscan tradition. He has to beg for food and lodging, and as a result of an insect bite, develops a lesion on his leg that will not heal.

In Mexico, he goes to the school of San Fernando, in Querétaro, and works in the five missions that have brought together some 3,500 members of the Pame people in the Sierra Madre Oriental. He learns indigenous tongues, organizes the catechesis and gets to baptize all the indigenous people welcomed in the missions. He does not only bring the Gospel; he teaches them farming methods, instructing them in new crops and cattle raising.

Fray Junípero knows how to take advantage of popular religiosity. The friar calls people to the mission with simple songs that remind the new faithful of the purpose of human existence. He travels almost 5,000 kilometers, always dragging his injured foot but never complaining.

In 1767, Fray Junípero leaves for California; one by one, he visits all the missions that the Franciscans had taken over from the Jesuits, who had been expelled by the Spanish crown. From Baja California, he travels north to the San Fernando Valley, where he establishes the first of the nine missions that would be born out of his missionary effort.

Nevertheless, Father Serra’s activities stir up jealousy and contradictions; the new Franciscan superior asks him to “moderate his fervent zeal,” and the bishop of California makes him hand over to the Dominicans all the missions in Baja California. The king’s representatives reproach him for “baptizing too many indigenous people.”

That is why, almost unable to walk, Fray Junípero returns to Mexico looking for support and assistance for the missions in California, which he feels are in danger. He has an interview with the Viceroy, Antonio María Bucarelli, and informs him of the state of the missions. His missionary zeal makes an impression on Bucarelli, who not only approves what Father Serra has done, but also authorizes him to establish new missions, among them Father Serra’s dream: San Francisco, which would rise next to the great bay on September 17, 1777.

His own religious superiors, however, want to control Fray Junípero’s missionary activity and limit his faculties as president of the California missions; he is not allowed to establish new ones “until further notice.” All the missions are placed under the control of a General Governor living in Sonora; even though Father Sierra has papal approval to do so, he is forbidden from imparting the sacrament of confirmation and receives orders to leave only one Franciscan friar per mission, bereft of community and support. Finally, he is instructed to leave control of the missions in the hands of the converted indigenous people, thus reducing the work of the Franciscans to spiritual or sacramental assistance only.

The “Padre Viejo” (Old Priest) as he was fondly called by the indigenous people, who was sick every day of his life, gathered strength from his faith and from his great love of Christ to be an exemplary religious, a very zealous missionary and a consummate holy man.

The great “evangelizer of the West” died at the Mission San Carlos Borromeo, in Monterrey, California, on August 28, 1784. His sainthood cause began in 1948; 10 years later, he was declared Venerable, and John Paul II proclaimed him Blessed in 1988. In September of this year, he will finally be canonized by Pope Francis during his pastoral visit to the United States; for this, he will use the papal privilege of “equivalent canonization” — that is, without the need for a second miracle — thanks to the proven popular veneration and saintly fame of Father Junípero Serra.

Comments from readers