By Jim Davis - Florida Catholic

Photography: JIM DAVIS | FC

MIAMI BEACH | St. Patrick, whose feast day is March 17, is one of the world's best-known saints. Yet much of what you’ve heard may be untrue.

For one thing, he wasn't Irish. For another, his birth name wasn't Patrick — it was Maewyn. He didn’t drive snakes out of Ireland. And he may not even have worn green.

Photographer: Jim Davis

St. Patrick's Church has a baldacchino, a high canopy, over its original altar.

Photographer: Jim Davis

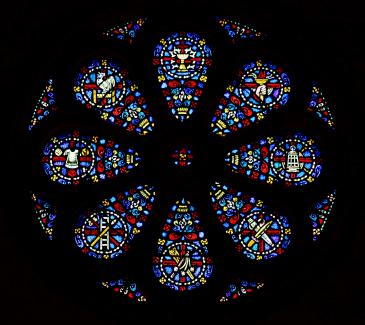

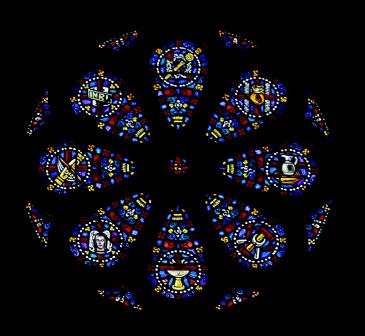

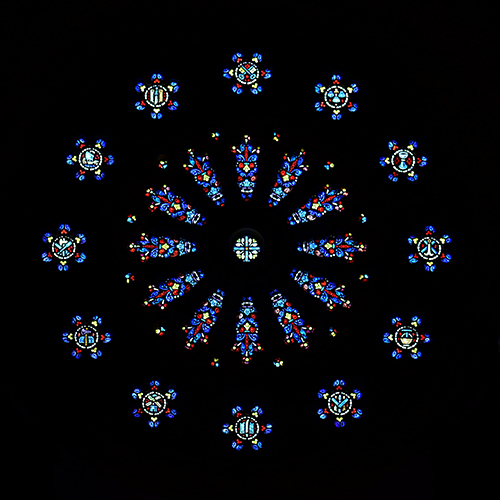

The rose window at St. Patrick Church resembles an ornate flower with 12 petals.

Photographer: Jim Davis

A painting inside the church office shows a haloed, ornately robed St. Patrick driving snakes out of Ireland.

The real-life man, namesake of St. Patrick Church on Miami Beach, was a model of courage, prayer and forgiveness. He was also a leader who founded Christian communities, then trained others who continued his work.

The story took place in the fifth century, when Maewyn was born to a deacon in Britain. Pirates kidnapped him, then sold him as a slave in Ireland. There, he worked as a shepherd, spending the lonely years in prayer and devotion to God.

Six years later he escaped back to Britain, but not forever: In a vision, he saw a man begging: "O holy youth, come and walk among us again." He went to school in France, then became Bishop Patrick — a version of Patricius, Latin for "Father" or "Head of Household."

Reaching Ireland's fierce Celts, however, took a bold approach. St. Palladius had already tried, given up and left for Scotland. But Patrick had his own methods.

First, according to legend, came a show of strength. In 433, he and his followers lit a bonfire near Tara, site of a pagan festival. The outraged King Laeghairé sent soldiers to arrest them — but to his shock, Patrick and his men marched into their midst, chanting.

Laeghairé didn’t convert (although some of his family did), but he gave Patrick permission to preach throughout Ireland. Over the next four decades, the bishop and his disciples built churches, founded monasteries, baptized thousands, and even brokered peace between local chieftains.

Other stories multiplied about St. Patrick as well:

- He drove all snakes out of Ireland, although none are believed to have ever been there.

- He fought off a horde of demons who tried to disrupt his prayer retreat on an island.

- He performed a thousand miracles during his time in Ireland.

- He used a shamrock, a three-leaf clover, to illustrate the godly Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Whatever the truth of those stories, historians say the saint didn’t wear green; he preferred a light shade called St. Patrick’s Blue. The change to green began around 1798, with the Irish Rebellion against England.

Patrick’s appeal even survived a literal gaffe, according to one tale. While baptizing a local prince, he accidentally stuck the pointed tip of his crosier into the man’s foot — causing it to gush blood — yet the prince didn’t flinch. When Patrick apologized for the injury, the prince said he thought it was part of the ceremony.

Patrick and his successors built a network of monks, monasteries and missionaries — 331 Irish saints, according to Catholic Online. They included the sixth-century St. Finian, whose monasteries turned out the so-called Twelve Apostles of Ireland.

They set an example for evangelization: humble but forthright in presenting the gospel while engaging the culture. They not only brought Ireland to Christ, but fanned out to other lands in Europe, Asia and Africa. Many Irish priests also came to Florida, where they served parishes in the dioceses of Miami and Palm Beach — and some still do.

On Miami Beach, the Ireland-born Father William Barry (later Msgr. Barry) celebrated a Mass in a theater in May 1926. His new flock caught the attention of Miami Beach developer Carl G. Fisher, who donated five polo stables to renovate for worship.

St. Patrick's took heavy damage in September that year from the hurricane that devastated South Florida and killed 392 people. The church structures were repaired, but Father Barry decided to build a proper church building.

The congregation moved into the building after its dedication Feb. 3, 1929 — by Father Barry's brother, Bishop Patrick Barry. A school, rectory, convent, recreation hall and auditorium soon followed.

St. Patrick Church won friends by continuing payments on its loans during the Great Depression of the 1930s. And during the 1940s, when Miami Beach became a military base, Father Barry gained respect by opening all parish facilities to the army. The parish also benefited from the postwar tourism boom.

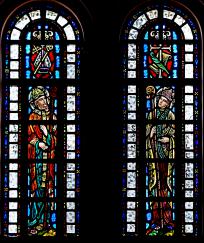

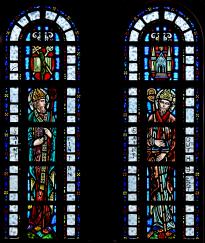

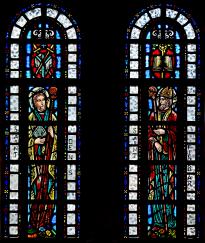

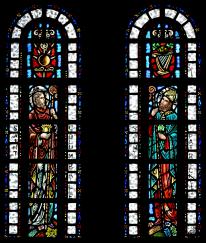

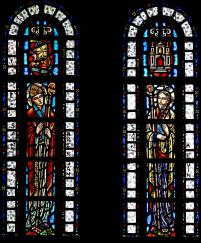

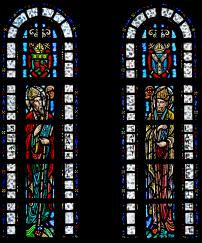

The parish weathered financial tough times again in the 1970s, then emerged with an award-winning school and renovations of its convent and stained-glass windows. In subsequent decades, the congregation launched a childcare center for preschoolers and increasingly served a growing Latino population.

St. Patrick Church even got to train a bishop. Father Rene H. Gracida pastored the church in 1971, then was consecrated auxiliary bishop of the archdiocese the following year. He later became the first bishop of Pensacola-Tallahassee, then of Corpus Christi, Texas. He retired in 1997.