By Cristina Cabrera Jarro -

Photography: CRISTINA CABRERA | FC

MIAMI | A bright white first Communion dress, a dainty doll, school photos: For some Cuban exiles, those treasures of a typical childhood come mingled with more ominous artifacts: small suitcases, passports, bunk beds.

The latter are reminders of their anguished separation from parents who were forced to make a dreadful choice: keep their children close or keep their children safe.

“When my daughter was eight, I turned to my mother-in-law and asked her how could she do it? How could she send my husband when he was eight to another country alone,” said Vicki Candelaria.

Her husband, Oscar, arrived in Miami in 1962. “They didn’t tell me where I was going or for how long,” he said. “Later I understood that they were sending me to a better place.”

Candelaria was one of more than 14,000 unaccompanied Cuban children who boarded airplanes bound for Miami between 1960 and 1962. Their parents chose to send them here � not knowing where in the U.S. they would wind up or if they would ever see them again � in order to save them from indoctrination by the island’s communist regime.

Over 50 years have passed since Operation Pedro Pan, the largest recorded exodus of unaccompanied minors in the Western Hemisphere. The boys and girls who came as refugees grew up to be men and women in exile. Their memories live on as they share their stories with family and friends. But as a group, they wished for a more permanent way to document their experience.

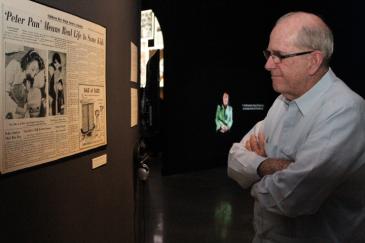

That wish turned into a tangible reality last month as the exhibit “Operation Pedro Pan: The Cuban Children’s Exodus” opened at the HistoryMiami museum downtown.

Photographer: CRISTINA CABRERA| FC

Carmen Romanach, left, was ecstatic to see two Sisters of St. Philip Neri who made all the difference for the children who were housed at the Florida City camps: Sister Paulina Montejo, center, and Sister Maria Victoria Ortega.

Photographer: CRISTINA CABRERA| FC

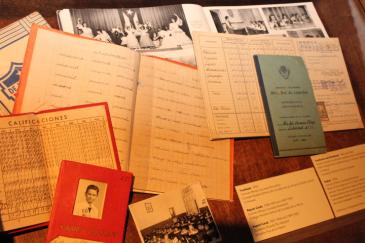

The foster camps that hosted the Pedro Pan children were filled with rows upon rows of bunk beds. At the Operation Pedro Pan exhibit showcased by HistoryMiami museum, visitors can also get a close look at suitcases, dolls, clothes and other artifacts brought by the children to the U.S.

Photographer: CRISTINA CABRERA| FC

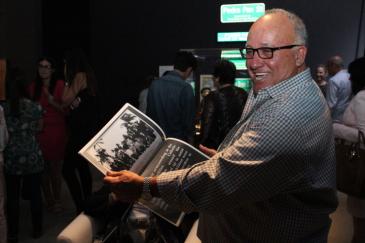

South Florida artist MANO stands by his "Faded Memory" painting and Maleta Project white suitcases. A Pedro Pan who left Cuba at the age of 12 with his brother, Mano said "Faded Memory" captures 53 years of emotions. His La Maleta Project is a traveling tribute to the 14,000 Pedro Pans. MANO hopes to obtain the signature of every living Pedro Pan.

On June 25, the museum opened its doors for a preview. Over 200 people attended, including a number of Pedro Pans who had donated personal belongings to the exhibit. Their eyes lit up as they walked in and saw their keepsakes on display.

Paco Echevarria found his first Communion photo at the same time his wife, Caridad “Cuqui” Ramos, found hers. “He was seven then. Look at him now, he’s 67,” she said.

The exhibit showcases a variety of artifacts including clothing, private letters, journals, documents, dolls, toys and photographs. Video vignettes of former Pedro Pans, such as former U.S. Senator Mel Martinez, Miami Mayor Tomas Regalado and Father Juan Sosa, pastor of St. Joseph Church in Miami Beach, also accompany the exhibit.

“The exhibit is engaging,” said Stuart Chase, president and CEO of HistoryMiami. “Our goal was to be emotional on the subject. They’re telling their stories as a first-hand narrative. There’s heart and soul here.”

Raquel Aveillez and her brother, Javier, share their grandmother’s joy at seeing her stories finally getting some limelight. Carmencita Romañach sits on the board of directors of Operation Pedro Pan Group, Inc., the organization that over the past five years has been largely responsible for collecting the artifacts and doing research for the exhibit.

“This is awesome,” said Raquel Aveillez. “She has always told us her stories and it must have been super hard not knowing the language. But everyone adapts.”

True, but the transition is often a rough one. Many Pedro Pan children had relatives waiting for them in the U.S. The thousands who didn’t were sent to foster homes or foster camps both here in South Florida and as far away as Washington state.

Sister Paulina Montejo and Sister Maria Victoria Ortega � two of the Sisters of St. Philip Neri who cared for the children at the Florida City camp � remember the children’s arrival.

“Many of them came in tears,” said Sister Paulina. “And bedtime was probably the worst. Some cried until one in the morning.”

The sisters did their best to keep up the children’s spirits. So great was their caregiving that decades later they are still recognized and loved.

Kelsi Candelaria, daughter of Oscar Candelaria, could not wait to meet the sisters who had welcomed and cared for her father. “It must have been emotional being a little child and to be welcomed like that. It’s incredible,” she said.

Msgr. Bryan O. Walsh, an Irish-born Miami priest, was at the forefront of Operation Pedro Pan. Authorized by the Department of State to sign the visa waivers that allowed the children to leave Cuba and enter the U.S., he made sure they were kept safe and cared for after their arrival.

“The man was a saint,” said Franklin Sosa, who arrived in October 1962. Sosa remained in Miami and eventually attended Archbishop Curley Notre Dame High School. He remembers how much Msgr. Walsh impacted his life and the lives of so many others.

One of them was Father Sosa, who arrived from Cuba in October 1961 and spent time at the Matecumbe and Kendall camps. When he was transferred to St. Raphael Hall, he met Msgr. Walsh, who was the chaplain.

“He gave me a home and it has been my only home,” said Father Sosa, who went on to complete his high school education at St. John Vianney Seminary in Miami before entering St. Vincent de Paul Regional Seminary in Boynton Beach.

Despite their struggles, most of the Pedro Pan generation have held onto their faith. It was, after all, the reason many of their parents sent them away, and trusted that the Church would take care of them.

“I am so grateful to God, to my parents and to the United States,” said Romañach. Had they not made that difficult decision, “none of this would have been possible today.”

GO AND SEE

- “Operation Pedro Pan: The Cuban Children’s Exodus” will be on view through Jan. 17, 2016 at HistoryMiami, located at 101 West Flagler St., Miami, 33130.

- Admission to the museum is $8 for adults, $7 for seniors and students with ID, $6 for children ages 6-12 and free for members and children under 6. Museum hours are: Monday-Saturday, 10 a.m.-5 p.m; Sunday, 12-5 p.m. For more information, call 305-375-1492 or visit historymiami.org.

- Learn more about Operation Pedro Pan Group, Inc. at www.pedropan.org or facebook.com/OPPGI.