By Jean Gonzalez - Florida Catholic - Orlando

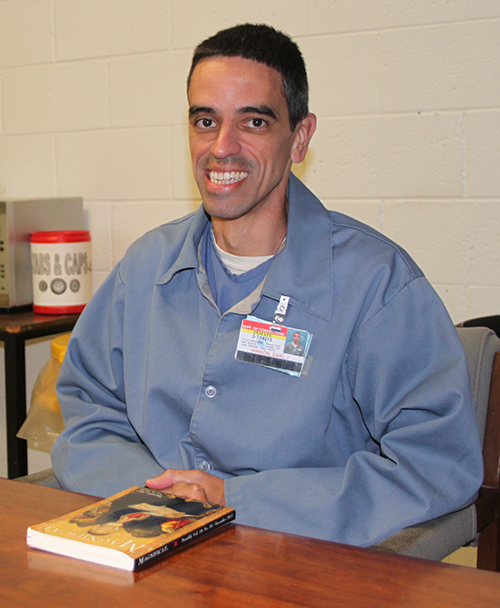

INDIANTOWN | Dressed in laundry-worn prison blues, Earl J. Hinson doesn’t stand out among fellow prisoners of Martin Correctional Institution. Thin and unassuming, his prison-issued light jacket looks a tad big on his 5-foot-7-inch frame.

Yet, as he sat down at a conference table of an interview room at the prison, located off the beaten path in Indiantown, two things immediately stand out � Hinson’s wide, genuine smile and the “Magnificat” book he carries with him always. He speaks about his relationship with God, Jesus and the Holy Spirit freely and with open frankness.

Photographer: JEAN GONZALEZ | FC

Earl J. Hinson sits for an interview at Martin Correctional Institution. With him is his Magnificat, which he carries with him most of the day.

Hinson is a “lifer,” sent to prison 16 ago years for horrendous crimes. In his time behind bars, this 37-year-old experienced a spiritual awakening that has led to receiving spiritual counseling, training in different ministry services and being present for counseling his fellow inmates. In November, the Diocese of Palm Beach named him Respect Life Person of the Year for his work in completing certification as a Rachel’s Vineyard facilitator, and helping facilitate more than a dozen retreats for inmates suffering from a post-abortion experience.

“Working in the midst of great darkness, our recipient has been a beacon of hope and a light of Christ,” said Don Kazimir, director of respect life for Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Palm Beach. “He has truly been a missionary to the many lost souls in the prison. He is known as the ‘go-to guy’ if you want to learn about God.”

Hinson is a changed man from the 22-year-old sentenced to life in prison for first-degree murder, attempted murder and armed robbery. But he cannot completely separate himself from the man who committed those crimes that left one man dead of a single gunshot wound to the back of the head, and another man critically wounded with 11 gunshot wounds. Another victim, a 16-year-old girl, escaped death because the gun put to the back of her head did not fire when the trigger was pulled.

“At my sentencing hearing, the mother of one of my victims � made the comment that I was a monster and looking at the facts of the case I can’t disagree with that,” Hinson recalled. “I really owe it to my victims and not just the ones of my crimes, but also my family and their families and friends and loved ones to kill that monster. � Society would want people like me locked up for the rest of my life because there is a genuine fear that I could go do something like that again. I have to make that an impossibility.”

Despite being the man who committed those crimes in 2000, Hinson has tried to live a life of conversion, and that path lies in a calling he believed he always had but never pursued or acknowledged � a calling to be a priest. While he is not eligible for the priesthood because he is a felon, Hinson said he could still live a life dictated by the tenets of vocation.

“What I try to do is live out my baptism as priest and prophet. I am offering my life as a sacrifice,” said the graduate of Tampa Catholic High School. “By living a priestly vocation as a sacrifice � to just say, ‘Lord I offer myself to you; use me up’ � is about the only option I have that can slay the monster who brought me to prison.”

How did he get here?

Hinson lays the blame at his own feet when it comes to his crimes. Yet, he does speak about his downward spiral that lead to the events of May 12-13, 2000.

From all accounts, he had a bright future. In a 2001 article by the St. Petersburg Times, his cross-country coach from Tampa Catholic recalled how surprised he was that Hinson was involved in a violent crime. When he heard about the events, he thought Hinson was the victim not the perpetrator.

But Hinson said his inability to deal with situations happening in his life, especially his relationship with his father and his parents’ divorce, led him to make one bad decision after another. He had no foundation of faith or a relationship with God to “fall back on,” and instead relied on bad decisions coupled with destructive behavior and violence.

“There was a series of lies I was telling myself, of who I was. What I needed to be or how I should I act. And I chose all the wrong influences during that timeframe to be my foundation and support those lies,” he said, admitting that the crimes were a “test run.”

“The one I really wanted to kill was my father. I just didn’t know if it was possible. If I could do it.”

He was arrested a day after the crimes � Mother’s Day. He was at his mother’s house spending an evening with her and his grandmother. Then the SWAT team showed up.

“As they arrested me, they were holding my mother at gunpoint. And it was very real to me how innocent people were being hurt by the choices I was making,” Hinson said, meaning not only the three victims of his crimes and their families, but people he would have classified as unrelated to the event because they weren’t there. “It really hit home when I saw my mother held at gunpoint. I am not an island. My decisions hurt innocent people.”

Locked up in county jail, Hinson had the first of many soul-searching experiences, asking the question, “How did I get here?” He was lying on the floor of the crowded jail cell and thought “physically and morally speaking it couldn’t get very worse.” But then he envisioned an abyss, and realized he could sink even lower by continuing on the same path, becoming an even more violent criminal in prison and causing more suffering.

But that wasn’t what Hinson wanted.

He did repent at that moment � sorry for his actions and the hurt they caused. He knew God could do better with his life than Hinson had done with his life for those first 22 years.

“To this day there’s been a great awareness for the loss I have caused, for the pain I have caused. Each day there is a greater contrition, a growing contrition,” he said, adding he won’t allow himself to forget about his victims. “I can’t pick up that eraser and say, ‘I wish it didn’t happen.’ I hurt them. They’re always going to remember. How dare I forget if they aren’t going to. How dare I forget them when they have the curse of remembering me at my worst.”

Transforming moments

Hinson said he has changed but will not release himself from the debt he owes his victims. In many ways, it is that spiritual debt that guided his conversion and leads him to serve others in prison.

He started studying his faith, Scripture, the works of the doctors of the Church and the saints, and it led him to transformation. The saints became a family to him, whose counsel he relied on.

He recalled a transforming moment when he was in the Hillsborough County Jail awaiting sentencing. He was reading the Gospels and he prayed to God about how does living the Gospel look in the 21st century.

“I asked, ‘Lord, send me somebody that I could emulate behind these walls, that I could see how this looks,’” Hinson said. “And I had this sense from the Holy Spirit of, ‘Be the example.’ And I would think, well, yes, that’s what I’m looking for, an example. But the Holy Spirit was consistent: ‘Be the example.’

“That’s been a push to me when I feel burnout or frustration or lazy, I have to be an example here,” Hinson continued. “I can’t ask people to be Christian and not be an example of a Christian myself.”

As Hinson speaks about being an example to others, he mentions prison ministers he has met who inspire him. He said his mother is also a great example of the faith. Although she suffered pain and sorrow for her son’s sins, she has not abandoned him and continues to travel an almost three-hour trip to visit him in prison every weekend, when possible.

One of the greatest examples of faith that Hinson ever witnessed came from a member of his victim’s family � the grandmother of Eduardo Natal, who Hinson killed. During the trial, prosecutors approached Natal’s family to tell them they wished to seek the death penalty in Hinson’s case. But Natal’s grandmother, the family matriarch, said the family was Catholic and didn’t believe in capital punishment. As a result, Hinson received life in prison without parole instead of death.

“It was a very tangible expression of faith on her part and it really rocked my world,” Hinson said. “In a sense of desperation, I was getting back into my faith and then she does that, and all the sudden all that matters is living my life like that.”

Prison ministry

To broaden his faith life, Hinson has sought services offered through Catholic prison ministry. Martin Correctional, where Hinson has been for nine years, is located within the Diocese of Palm Beach, where Deacon Don Battiston serves as a Catholic chaplain.

Some eight years ago, Tom Lawlor, the now retired diocesan director of prison ministry, approached a volunteer, Donna Gardner, about bringing Rachel’s Vineyard, a post-abortion healing ministry, within the prison. Gardner, who now works in private practice but until September 2016 worked as diocesan director of Rachel’s Vineyard for 16 years, said the experiment to bring the ministry behind bars proved to be fruitful, as many prisoners had experiences with abortion and sought healing.

One of those men was Hinson. When he was 18, and just out of high school, he got a call from a girl he had dated. She was pregnant and she was going to get an abortion. At the time, Hinson breathed a sigh of relief, did nothing to stop it and hung up the phone.

He didn’t think about it again until he was in prayer and incarcerated. The experience was not as cut and dried as he thought. Hinson felt a sense of powerlessness and believed his inability to care about the girlfriend, his unborn child and the act of abortion became part of the central lie that caused him to lash out and become violent.

When the opportunity to participate in Rachel’s Vineyard surfaced, Hinson was eager to participate in the retreat experience tailored for the prison setting into 10-week sessions. But so were other inmates. Hinson would have to wait until the third round of classes to participate.

“It was more than I could have expected. Through the program I was able to have an encounter with my daughter and who she is. It floored me,” he said.

Gardner described Hinson as a “super personable” guy who truly had a relationship with the Lord and the Blessed Mother. She also recognized his strong leadership skills, and it sparked her to ask Lawlor about the possibility of developing a Rachel’s Vineyard leadership “inside team” � retreat leaders who are prisoners themselves.

“The thought was the inmates could continue to minister to their brothers as they go through Rachel’s Vineyard,” Gardner said. “(Hinson) went through the same rigorous training that all go through on the outside. � It is a yearlong process and he did great. He has been an incredible minister in the prison and is helping build a beautiful culture of life behind the walls.”

Lawlor agreed Hinson is an asset to Rachel’s Vineyard and to many prison ministry programs because he lives an “absolutely legitimate” faith life. “He truly brings the light of Christ into a dark environment,” Lawlor said, adding Hinson is a perfect example of why the death penalty is not necessary and should not be used. “It is during his incarceration that he brought his life back to Christ. The way he is living his life, he is a living example of the faith 24 hours a day, seven days a week, in a place no one else can reach. That wouldn’t be possible if he was given the death penalty.”

Hinson described his experience with Rachel’s Vineyard as a “vocation inside a vocation.” It is not the only ministry he has served. Just before participating in Rachel’s Vineyard, he was teaching a creative writing class to inmates to help give voice to their thoughts and possibly have a project to work on when they leave prison. He has served as an orderly for the prison chaplain, in which he assists with day-to-day activities. He previously facilitated the prison’s DIRECT program � which stands for Direct Involvement Reduces the Effects of Criminal Thinking � a behavior modification program that analyzes the motivations for thinking patterns based on the 40 years of study of criminals performed by psychologists Stanley Samenow and Samuel Yochelson.

And when the Welcome Home Initiative for prisoners who are also veterans exhibiting Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder was established in the prison, Hinson was asked to help facilitate and live in an dorm setting with veterans in the program. As such, he is able to be available for counseling 24/7.

Intrinsic value

According to the Florida Department of Corrections, Hinson is one of 1,339 inmates living at Martin Correctional Institution. Of that population, Hinson is part of the roughly 27 percent who are lifers.

Ministry to the incarcerated is not an easy calling and it can have a negative connotation. It means ministering to criminals, some of whom are serving their second or third term, some of whom will not see outside the walls for decades and some, like Hinson, who will never again see the outside of prison walls. Labels such as lost souls and limited futures might pigeonhole the ministry and those served.

That might be another reason why Hinson’s calling is even more satisfying and crucial. He said it is easy to relate to the prisoners because they are him.

“I know I am a living, breathing human being and I know I have an intrinsic value, because that is what I feel in myself. Since I know that truth, the first thing I try to do is to treat them by telling them that truth � that they are somebody worth knowing, that they are a living, breathing human beings,” Hinson said. “The most critical thing to help them grow in this environment where they have the chance to heal themselves and maybe come to contrition for their crimes and sins is that Jesus is a living, breathing person � reaching out for us, to have a personal relationship with us.”

Hinson references St. Thomas Aquinas as he describes a philosophy of prayer in which he said it is possible that his life and the lives of his fellow lifers could be compared to that of cloistered monks.

“Like monks who have cloistered themselves, we have the opportunity to lift the world up in prayer. We have the opportunity to lift our victims, our families, our pains, justices and injustices,” he said. “Some men are spiritually inclined and take to that rather quickly. Other men, it takes time to develop. The good news is that they are a captive audience. You really cling to Jesus or you cling to the dark, depression of this environment.”

Praying for his victims is a critical part of Hinson’s life because the way the incarceration system operates, he is not able to contact them, even if it is in an act of contrition. He would welcome them contacting him, even if it would be to lash out at him because that might help them heal.

But he knows their healing is out of his hands. He is “betting the whole house” on the “miraculous reality that Jesus heals,” even if his victims never forgive him.

“I think about that night and morning regularly, and I make it part of my prayer life. I walk through those memories with Jesus, and I ask Jesus to touch them with healing, to help them,” he said. “I can still choose to grow closer to Jesus so that his grace can take care of them. As long as I continue to convert to the Lord and offer them up in prayer, nothing is impossible with him.”