By Tom Tracy - Florida Catholic

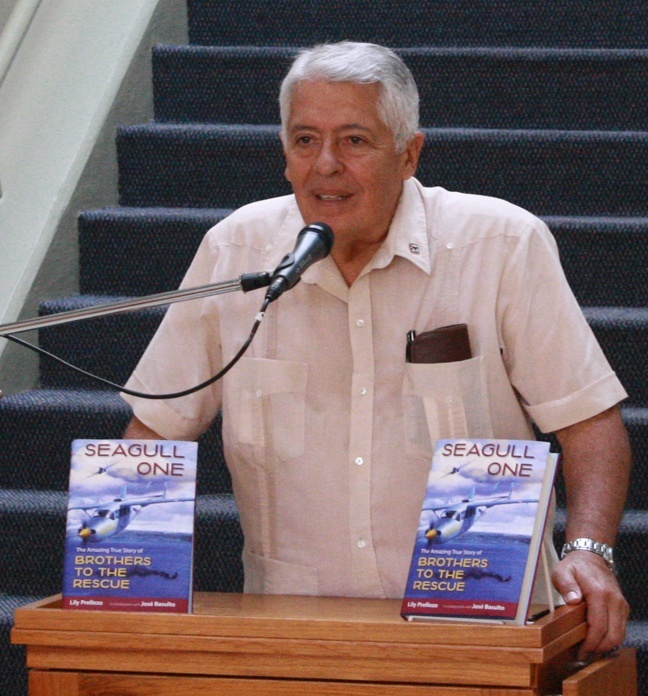

Photographer: JONATHAN SANCHEZ | COURTESY PHOTO

Jose Basulto, founder of Brothers to the Rescue, speaks at St. Thomas University during a Hispanic heritage event. His group is the subject of a new book, "Seagull One: The Amazing True Story of Brothers to the Rescue".

MIAMI GARDENS � Two decades after their founding and eight years since they last flew together over the Florida Straits, the head of Brothers to the Rescue said the volunteer pilots� organization had become an example of non-violent resistance for social change.

�Today we are sharing a message that people can solve their own problems. You also can be Brothers to the Rescue and create your own help organizations,� said Jose Basulto, the Cuban-exile and veteran of the Bay of Pigs invasion whose organization estimates it saved some 4,200 rafters fleeing Cuba during the 1990s.

�The experience of saving someone in the Straits of Florida was something that stays with you � we were hunting to save lives,� said Basulto.

The Miami businessman led teams of mostly young volunteer pilots of 19 nationalities operating out of south Florida airports. They frequently flew into Cuban airspace on their search and rescue missions. But in 1996, while reportedly not in Cuban airspace, the Cuban military shot down two of the planes while Basulto�s plane escaped.

The murder of the four men in those planes � three U.S. citizens and one legal resident � received worldwide condemnation. It also led to a lawsuit on behalf of the victims� families, who were awarded monetary compensation from the Cuban government.

Photographer: COURTESY PHOTO

Lily Prellezo, a Miami Catholic, collaborated with Jose Basulto to write her first book, "Seagull One: The Amazing True Story of Brothers to the Rescue."

A part of the pro-life speakers� bureau for the Archdiocese of Miami and today a writer, Prellezo said she never flew with the pilots during their active years but met them through a mutual friend. Basulto asked her to tell his story in a book project � her first.

The result is "Seagull One: The Amazing True Story of Brothers to the Rescue" (University Press of Florida), in which Prellezo worked with Basulto to compile an official history of the organization. She has been invited to speak at the upcoming Miami International Book Fair in Miami, Nov. 12-21.

�It wasn�t a bunch of old Cuban guys flying around,� Prellezo said of Brothers to the Rescue, pointing out the diverse backgrounds of men and women pilots in simple Cessna aircraft. Some initially were motivated by the chance to rack up free flying hours but eventually team members were united in sympathy for the Cuban rafters who were often perishing in their attempts to flee Cuba.

Basulto, Prellezo noted, was a U.S. Army veteran who once trained and worked with the CIA as a freedom fighter and drove a power boat from Miami to Havana to bomb a hotel full of Russians. But he had evolved in his thinking while helping the Nicaraguan Contras in the 1980s.

�One day he had an epiphany while working with the Contras of Nicaragua. He started to read the writings of Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., and he embraced the nonviolence movement,� Prellezo said, adding that she did not know about St. Thomas University�s institutional roots in Havana until her invitation to speak there Oct. 21.

The title Seagull One refers to Basulto, whose radio call sign and aircraft, a twin-engine Cessna, go by the same name. The plane was ultimately auctioned off at a charity for $100,000 and donated to the Sisters of Charity who reportedly used the funds to help people in Haiti and Cuba following hurricanes there.

Three Argentine brothers, the Lares brothers, were the star pilots of the organization. The pilots, who sometimes referred to God as the �co-pilot of Brothers to the Rescue,� were credited with spotting many of the rafters.

�My eyes were not that good. There were young pilots were very good vision. Everyone has a mission in life,� Basulto said of the younger pilots. The youngest of the Lares brothers, however, was tragically crippled after crashing in the Everglades on a Christmas Eve mission.

Basulto said he never ruled out the possibility that saboteurs had tinkered with the aircraft that led to the crash. And he is certain that there were periodically Cuban and FBI spies within the organization, which had been accused of trying to provoke international incidents with Cuba. The Cuban government unsuccessfully tried to sow dissension within Brothers to the Rescue, he added.

In addition to looking for rafters, the pilots sometimes managed to drop pro-democracy leaflets into Havana.

�We became a terrible enemy of the (Cuban) government but we had three goals: to save lives, promote solidarity with the Cubans on the island and to take journalists with us to educate the world press on the suffering of Cubans as well as to discredit the message of the Cuban government.�

Basulto said he has vigorously researched the 1996 shoot-down incident but only obtained heavily edited documents through the Freedom of Information Act. He maintains that the facts indicate the U.S. did not take any steps to prevent the Cuban air force from shooting down his pilots.

�It wasn�t the first time we were inside that airspace to save lives. We did that many times, flying three to four times a week with several planes,� he said.

Over the years, Basulto learned that it was necessary to intercept the rafters early-on in their journey, because they often did not survive beyond three or four days before succumbing to dehydration and exposure. �I found a group who were out there seven days; after five days they are hallucinating, so we wanted to find them earlier.�

Politics eventually halted the flow of rafters. A revision to the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966 stipulated new rules. After talks with the Cuban government, the Clinton administration came to an agreement with Cuba that it would stop admitting people found at sea. It became known as the "wet foot, dry foot" policy: a Cuban caught on the waters between the two nations would be sent home or to a third country.

In 2003, Basulto and others flew their final operations in a symbolic anniversary tour, dropping more leaflets into Cuba.

Tom Tracy flew with Brothers to the Rescue in the early 1990s.

Photographer: JONATHAN SANCHEZ | COURTESY PHOTO

Jose Basulto, founder of Brothers to the Rescue, left, and Lily Prellezo, a south Florida Catholic and author of "Seagull One: The Amazing True Story of Brothers to the Rescue", pose with Msgr. Franklyn Casale, president of St. Thomas University, after a Hispanic heritage event on campus.