By Florida Catholic staff - Florida Catholic

Photographer: FILE PHOTO

With date palms rising in the distance, Archbishop Joseph P. Hurley celebrates Mass atop an improvised altar in one of many rural arreas he purchased to build the Catholic Church in Florida.

Related stories:

- Archbishop Hurley: prophetic vision, pragmatic organizational skills

- Priest recalls visionary leader of Florida Church

ST. AUGUSTINE | He’s called the “builder bishop” because in his 27 years leading the Diocese of St. Augustine, Archbishop Joseph P. Hurley more than doubled the number of parishes and tripled the number of schools. Then, with tremendous foresight, he anticipated the growth around the state and bought thousands of acres of land when it was still inexpensive for future parishes and schools.

Though he’s been dead 50 years, the organizations he started or fostered are still flourishing: 74 parishes, 100 schools, Catholic Charities, the land purchase for St. Vincent de Paul Regional Seminary and much more.

But Archbishop Hurley also was a Vatican diplomat, which took him to India and Japan, to Rome during the tense years leading up to World War II and after the war to Yugoslavia during the rise of communism.

Heady stuff for the son of Irish immigrants, one of 11 children. Growing up in a poor neighborhood in Cleveland, Ohio, he developed a strong moral compass and sense of patriotism.

When he was ordained in 1919, Hurley probably expected his ministry to play out in the parishes of the Cleveland diocese. But in 1927, a former seminary professor, Archbishop Edward Mooney, recently name apostolic delegate to India, asked Hurley to be his secretary. The poor boy from Cleveland said yes.

The assignment to India launched him on an improbable diplomatic career, said Jesuit Father Charles Gallagher, author of Vatican Secret Diplomacy: Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII. Traditionally Vatican diplomats are formally trained, studying canon law, foreign languages and the history and cultures of other countries. Though Hurley did briefly study diplomacy in France, his real training was on the job.

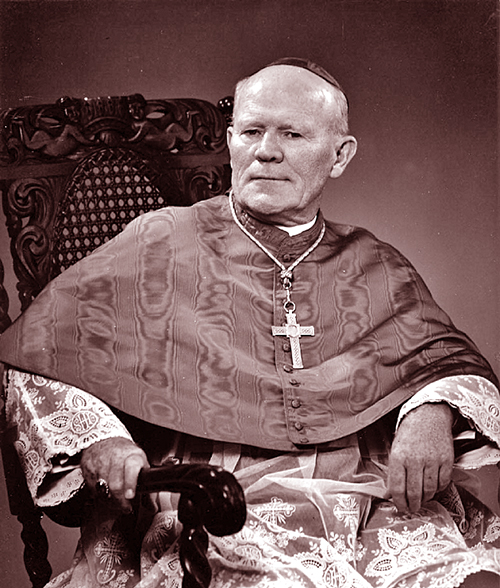

Photographer: FILE PHOTO

Archbishop Joseph P. Hurley in his formal portrait. He was a Vatican diplomat and bishop of St. Augustine, which until 1958 then encompassed the whole state of Florida, from 1940 to 1967.

After five years in India, Mooney was named apostolic delegate to Japan and Hurley accompanied him. In 1933 when Mooney was named Bishop of Rochester, N.Y., Hurley stayed on in Tokyo as chargé d’affaires. In 1934, he moved to the Vatican as the American liaison in the Secretariat of State. Hurley was only the second American attaché in the Vatican. His successor was Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York.

In the 1930s, the U.S. and the Vatican did not yet have diplomatic ties and were, in fact, wary of each other, Gallagher said. Not yet a superpower, the U.S. in the 1930s was predominantly Protestant with a strong anti-Catholic streak. But in the tumultuous years leading up to the outbreak of World War II, the U.S. and the Vatican saw the value of closer ties.

EMBRACE DEMOCRACY

During the next six years, Hurley was the go-between. In the process, he developed a close bond with Pope Pius XI and valuable ties with the U.S. State Department.

“Hurley was able to see the value of democracy in a way that Pius was not,” Father Gallagher said. “He believed the democratic system could benefit Catholics and thought Catholics ought to stop being skeptical of democracy and embrace it.”

Hurley also felt strongly that the Vatican should take a firm stand against the Nazis and Fascists and he was encouraged that Pius XI was speaking out. But in February 1939, Pius died. A month later Eugenio Pacelli, a veteran diplomat, was elected Pius XII. Six months later the Nazis invaded Poland.

The Vatican was between a rock and a hard place ’┐Į literally. Even as Nazis swept through Europe and the Fascists seized control of Italy, Pope Pius XII argued against war and ardently maintained a policy of neutrality, Gallagher said.

Many in the Vatican were more worried about the communists, who openly persecuted the church. But not Hurley. Though no fan of the communists, Hurley considered Hitler public enemy No. 1.

Hurley frantically tried to nudge the new pope into taking a stronger position against the Nazis. But Pius XII resisted. In utter frustration, Hurley went on Vatican Radio and delivered a strong anti-Nazi speech. It was a career changer.

Out of the blue, in August 1940, Pius XII elevated Hurley to bishop and assigned him to the Diocese of St. Augustine. In his 13 years in the diplomatic corps, Hurley had lived and explored Asia and Europe, but he had to look at a map to find St. Augustine, Fla.

THE BOONIES

Though St. Augustine was a popular tourist town, to a world traveler like Hurley, it must have seemed like a backwater, said Gallagher. This was Florida before interstates, air-conditioning and shopping malls.

Hurley quickly found his footing. A bishop in the boonies is still a bishop, and he now had a pulpit of his own and a diocesan newspaper, the Florida Catholic. He got in touch with his old friends in Washington, including Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles.

In 1940, the U.S. was still on the sidelines of World War II, and the country was embroiled in the dilemma of whether to intervene in Europe. Unlike his brother bishops, Hurley clearly favored President Franklin Roosevelt’s policy of intervention. The State Department was delighted to have an outspoken ally and quietly supplied him with the latest information by courier that Hurley used in newspaper columns, sermons and radio speeches.

Photographer: FILE PHOTO

Then Bishop Joseph P. Hurley rises and bows as Archbishop Alojzijc Stepinac of Zagreb, Yugoslavia, enters a Zagreb courtroom, Oct. 11, 1946. He was being tried on charges of collaborating with the Axis.

Gallagher describes Hurley’s relationship with the Roosevelt administration as a “secret embrace.” Not even his old friend and mentor Archbishop (later Cardinal) Mooney understood Hurley’s role. “Mooney knew Hurley was in touch with Welles, but he didn’t know Welles was calling the shots.

“Hurley knew that if his relationship with the State Department became public, the church would be open to criticism,” Gallagher said. “And it was already a time of great anti-Catholic sentiment.”

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor changed the dynamics. The debate was over; the U.S. joined the war. Throughout the war, Hurley continued to speak out strongly against the Nazis and was one of the first to raise the alarm that the Nazis were sending Jews to concentration camps.

DIPLOMATIC SERVICE

Shortly after the end of the war, the Vatican recalled Hurley to diplomatic service. Pius XII named him Regent ad interim in Yugoslavia, where Communist dictator Marshal Josip Broz Tito had come to power and was persecuting the church.

“They had to have an American because after 1945 the U.S. was the superpower,” Gallagher said. “Marshal Tito insisted on an anti-Fascist, which meant none of the Italian diplomats could be considered.”

When they looked at candidates, there was only one man for the job ’┐Į Joseph P. Hurley.

“Ironically Pius XII and his fellow diplomats had no knowledge of Hurley’s secret work with the State Department in 1940-41. It was an act of subterfuge and if they had known that they would never have accepted him back,” Gallagher said.

The other irony was that Tito believed Hurley would be friendly to his point of view, Gallagher said. With Nazism vanquished, Hurley was under no illusions that communism was now the new geopolitical enemy of Roman Catholicism.

Pius XII equipped Hurley with enormous power as regent. Unlike a nuncio, a regent can make decisions without consulting the Vatican.

“It was an intense assignment for Hurley. The sort of assignment that would break most weak-willed people,” Gallagher said. “I don’t think he gets the credit he deserves as a papal diplomat.”

During the next four years, Hurley did his best to become a thorn in Tito’s side. By Vatican count, Tito killed 243 priests and at least one nun. Of the more than 160 other priests who were imprisoned, the most famous was Archbishop (later Cardinal) Alojzije Stepinac of Zagreb.

Hurley was able to make Stepinac a problem for Tito’s foreign policy by linking it to American public opinion and endangering his foreign aid, Gallagher said.

Despite Hurley’s efforts to get him released, Tito put Stepinac on trial for treason. Each day as Stepinac was led in and out of the courtroom, Hurley bowed in respect, a gesture that infuriated Tito and it was captured in a wire service photograph published around the world. Stepinac was convicted and sentenced to prison. He was released after five years.

Hurley also tried to influence the State Department’s evolving policy toward Yugoslavia but his position no longer aligned with U.S. foreign policy. His influence with the Vatican was waning, too. In 1949, Pius XII gave him the title of archbishop, but not an archdiocese to go with it.

Archbishop Hurley returned to St. Augustine where there was important work to be done. He had a diocese to build.

Lilla Ross writes for the St. Augustine Catholic, the bimonthly magazine of the Diocese of St. Augustine.

Photographer: FILE PHOTO

From the personal collection of Archbishop Joseph P. Hurley's niece, Mercedes Hughes, this photo was taken in December 1953 at Immaculate Conception School in St. Petersburg, an African-American parish that later merged with St. Joseph in Tampa.