New English Missal translation removes the

Credo: I believe

Monday, October 31, 2011

*Msgr. Richard Antall

Credo is “I believe.” So during the Mass I am going to profess my faith before the community that shares the same beliefs but expects my personal affirmation. This is not a change in translation, because strictly speaking, “credo” does not translate as “we believe.” The word “credo” in Latin means “I believe.”

Therefore the change of language in the new translation of the Mass marks a return to the original meaning of the Credo, or Creed. It is a correction, and it should make us think about what we speak. “This is what I believe.”

Once I went to the funeral of a Lutheran relative, a woman who had suffered much in her life because of the ingratitude of someone very close to her. The minister included the Creed in the funeral service, saying that the deceased had lived the belief we were about to profess. I found the expression of the Creed at the service to be very moving and significant, for it was saying: “This is what made her tick,” and at the same time, “We are with her. The Creed makes sense of our lives, too.”

This happened shortly after a friend of mine said that her priest, one of those “creative” types from the ‘60s, had dispensed with the Creed at Mass because “most people don’t know what the words mean.” He was probably right, but he should have remembered that it was his job to help the people understand what the words mean.

All liturgical reform is about “active and conscious participation.” That, wrote Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, better known now as Pope Benedict XVI, means a process of interiorization. He said that, as far as liturgy goes, we all need “an education toward inwardness.”

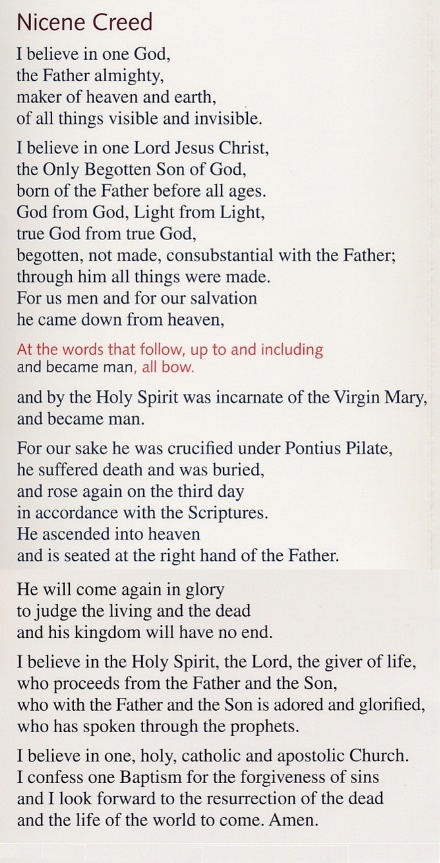

The interiorization of the Creed means that my world view, my basic understanding is that God exists; He is the Father and Creator of the world; his Son became incarnate and shared our human nature, and suffered and died and will come again in glory to judge us, and his kingdom will have no end; the Holy Spirit is the Lord, the giver of life; the Church, one, holy, Catholic and apostolic is part of God’s divine dispensation; divine forgiveness is experienced in baptism; and we live expecting the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.

Victor Frankl, the famous Viennese psychiatrist who survived the Nazi death camps, observed that his fellow survivors almost always were people who believed in something beyond themselves. His conclusions, written in his book, “Man’s Search for Meaning,” are very much compatible with the Christian understanding of hope and applicable even to the simple act of reciting the Creed in community once a week with fellow believers.

There is a revival of atheism in the world today that is disturbing in its gross vulgarity. One prominent atheist writer has even written an attack on Blessed Theresa of Calcutta with a sexual double entendre as a title.

While this is not the first time in history when it has been fashionable in so-called cultured circles to be against belief, it is something quite new in America. Voltaire and Diderot are names to us. Even Bertrand Russell, who famously stated, “I believe that when I die I shall rot and nothing of my ego will survive,” is a figure from books. The fact that today real live atheists fill bookshops and sign copies of their dismal screeds for their even more dismal fans is something quite shocking.

That is why our own profession of faith needs to be taken seriously. When I was a boy, I remember being worried about Khrushchev’s atheism and the deathly struggle between communism and democracy. A public bus I rode infrequently had a sign with the Russian’s picture and his famous threat to America, “We will bury you.” That was the face of atheism. Now it is another picture that comes to mind when we talk about the rejection of God.

There is a “practical atheism” that stalks our land, in the words of a former spiritual director from my seminary. So many act “as though” there were no God. In the day to day betrayal of truth and charity which is our social life, there are many decisions that are taken “as if God did not exist.”

A Catholic politician or a Catholic voter believes in God and admits he does not countenance the willful destruction of life in the womb. These people say, “Abortion is wrong,” but they do nothing about it. You cannot smoke in many public places because of the harm you may do to third parties, but the child in the womb — even that child who could survive outside the womb — can be destroyed at will in our country.

“Practical atheism,” that is “atheism in practice,” allows one to be personally convinced of an evil that causes innocent parties to suffer but not do anything, because God is hypothetically removed from the equation. The pretension is: Others have no faith in the transcendent and therefore can violate values that I consider absolute but they do not. The reality is: I am acting as if I do not believe either that God cares or that he exists.

Our profession of faith is an antidote to the practical atheism of our times. Our search for meaning has come to a happy conclusion. That does not mean it is not a struggle to believe. Faith demands sacrifices. If someone wanted to know our core beliefs, they should not have to go much further than the Creed of the Mass.

Changing “we believe” to “I believe” is not going to make a great deal of difference in the world perhaps. Nevertheless, if it makes us think about what we truly believe and emphasizes a personal commitment, it can bring about a change in us.

Comments from readers