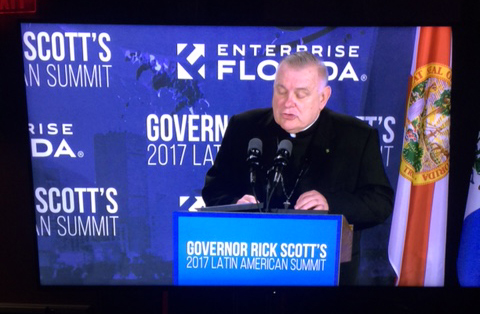

By Archbishop Thomas Wenski - The Archdiocese of Miami

Archbishop Thomas Wenski gave this talk at Fla. Gov. Rick Scott’s 2017 Latin America Summit, held Oct. 2 in Miami.

I remember once I was talking to a grad student who said he was studying for a degree in Latin American Studies. When I mentioned to him that I was a Catholic bishop, he looked at me with a blank stare. He had no idea of what or who a Catholic bishop was. Now, I didn’t really say anything to him; but I thought about all that money his parents wasted on his university studies � because how could anyone “understand” Latin America without some understanding of the Catholic Church and its role in the shaping of the culture that we call Hispanic. The history of the Catholic Church in Latin America � like anywhere else � has of course both lights and shadows. But without necessarily denying the contributions of other faiths, including the indigenous religions and the influence of African religions, the presence of Judaism and the growth of evangelical churches, the influence of the Catholic Church � and its institutions � is unequaled in Latin America.

Archbishop Thomas Wenski delivers his talk at Fla. Gov. Rick Scott’s 2017 Latin America Summit, held Oct. 2 in Miami.

So, when we in the American Church evaluate policies affecting Latin America, we, first, look to the local Church for guidance. They are on the scene and have been since day one; I expect that the Church will remain on the scene � and they understand contexts of whatever situation. Again, the value of the local Church’s perspective is inestimable: There is no other reality on the scene as present in the daily lives of the region’s people or as credible. Think about it, in most of these countries there are only two institutions that have a presence and an influence throughout the country � the military and the Catholic Church. With its schools, its clinics and hospitals, its parishes and mission outposts, the Church is involved in promoting the life and dignity of the human person � and still offers hope in a continent where economic stagnation, grinding poverty, corruption, social inequality often lead its people to seek conditions worthy of human life in the north.

I have been traveling to Cuba since the mid-1990s � (in fact, I got back last night. I was there over the weekend to attend the ordination of a new bishop in Ciego de Avila).

There, the Catholic Church is practically the only independent institution on the island; and in that sense, it is, and will continue to be an incubator of civil society. And civil society must grow if Cuba is to successfully transition from a totalitarian form of government to a more democratic one. The Church is helping to grow civil society � through libraries, independent publications, Caritas (social service) programs, etc.

And the Church wants a “soft landing” for Cuba � and thus the bishops of Cuba have opposed the embargo and favor engagement rather than isolation. And so the Cuban church has welcomed the reestablishment of relations between US and Cuba. Religious freedom is still much restricted in Cuba � it’s better than what it used to be (Pope John Paul II’s visit in 1998 marks a “before” and “after” in relations between the Cuban state and the Catholic Church); but it’s not what it should be. But since the 1990s the Church has been gaining new space � and hopes to continue to do so. Today, from its own meager resources, it is helping with the recovery after Hurricane Irma. Parishioners from Maisi, the eastern most tip of Cuba, loaded up a truck with malanga and plantains and brought it to the Caritas of Camaguey. Later this week I hope to send about 8 chainsaws to the archbishop of Camaguey. (If nuns here in Miami can wield chainsaws, so can bishops and priests in Cuba.)

Moving to another country in the region, the Holy See, along with the Venezuelan bishops, has been actively searching for a solution to the rapidly deteriorating political, economic, and social situation in Venezuela. The initiatives of the Holy See were seemingly manipulated by the Maduro government and while the Venezuelan Church continues to call for dialogue and restraint as the government and the opposition are locked in conflict, the bishops have vocally denounced the increasingly bloody crackdowns, and have called for national discernment and legal preservation of the morally legitimate options of peaceful civil disobedience and civic protest. Because of their denunciations, the Conference headquarters of the Venezuelan bishops has been ransacked, some priests have been harassed and threatened with physical harm � there is no question whose side the bishops are on. If in Cuba, the Catholic Church is working to rebuild civil society, in Venezuela it is working to preserve it.

Pope Francis was in Colombia earlier this month. Here in Miami we were distracted by hurricane Irma but his visit was an important one � and one that, I believed, moved the needle significantly in helping secure the success of the Peace Accords.

Not every Catholic or every bishop is in agreement with the Accords in the form that they were signed in Havana � and that were defeated in the referendum last year. But the Church in Colombia has been working for peace and reconciliation from the beginning of the conflict. While FARC has laid down their arms last year, the ELN (Ejercito de Liberacion Nacional) were scheduled to effect a ceasefire on October 1, 2017. The Church in Colombia is actively taking part in the discussions with the ELN, at the request both of the ELN and the government.

And if you would ask the Church in Colombia � and our statesmen should ask them � they would probably say something like: The United States can make a significant contribution to the consolidation of peace and stability by focusing its foreign assistance on social and economic development, as well as continuing to provide aid to internally displaced persons. U.S. aid should assist equitable economic development by supporting the extension of democratic and legal institutions in rural areas, promoting reconciliation through effective transitional justice mechanisms, and ensuring the long-term resilience of the countryside through sustainable environmental initiatives.

Throughout Latin America, the Catholic Church continues to be a voice for the voiceless; but the Church doesn’t just talk the talk, it walks the walk. Each country has its uniqueness � and so the Catholic Church in each country is also unique � and if at one time the Church could have been criticized for being a “foreign” presence because the clergy were mostly missionaries from other countries, today it is a “criollo” Church, more and more inculturated � that is to say, Cuban in Cuba, Venezuelan in Venezuela, Colombia in Colombia � and for that reason the Catholic Church can be an honest broker in helping those who want to help human flourishing in these lands evaluate what can and what should be done. The Church is uniquely situated to “see” reality from the ground � with as Pope Francis would say “the smell of the sheep”; but also the Church can see the perspective from above, from even more than 30,000 feet.

Comments from readers